Your rival will bleed you to death’ - a global consultancy firm that Dabur hired had warned the company in 2001. Dabur was only trying to identify the future pillars of growth. The chyawanprash-maker and homegrown FMCG player, which had a sizeable presence in the toothpowder segment with its Lal Dant Manjan since 1930, was keen to enter into the toothpaste category.

For Dabur, though, it was a Catch-22 situation: Powder was predicted to come to a grinding halt, and the probability of being squeezed out of the tube by the ‘Big Boy’ Colgate, on the other hand, was high. Mohit Malhotra, who was then part of the marketing team and closely working with the consultancy firm on the project, saw the threat. “It was real,” recalls Malhotra, who was made chief executive officer last year. “But so was the opportunity.”

Two years later, Dabur bit the bullet. It reached out to its loyal customers of dant manjan with a new communication, and proposition: Aapka manjan ab paste mein aaya. (Your powder now comes in the form of paste.) Though launched without hiccups, Dabur didn’t paint the town red.

Reason: A lot happened in the prelude to the launch. Lal Manjan was red in colour because of a herbal ingredient and spitting it would cause stains. So when powder got converted into paste, both the properties remained. Consequently, the option of ditching red for white was explored. Add to this the result of an internal survey done by the company before the rollout: Users either loved it or hated it. “It had a stinging flavour, a cooling after-taste, and was polarising,” recounts Malhotra, adding that the company had set a conservative sales target of ₹5 crore for the brand. One year into operations, the brand clocked ₹15 crore.

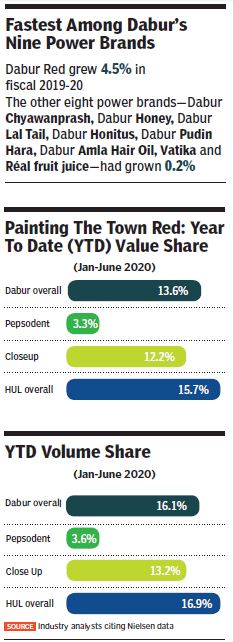

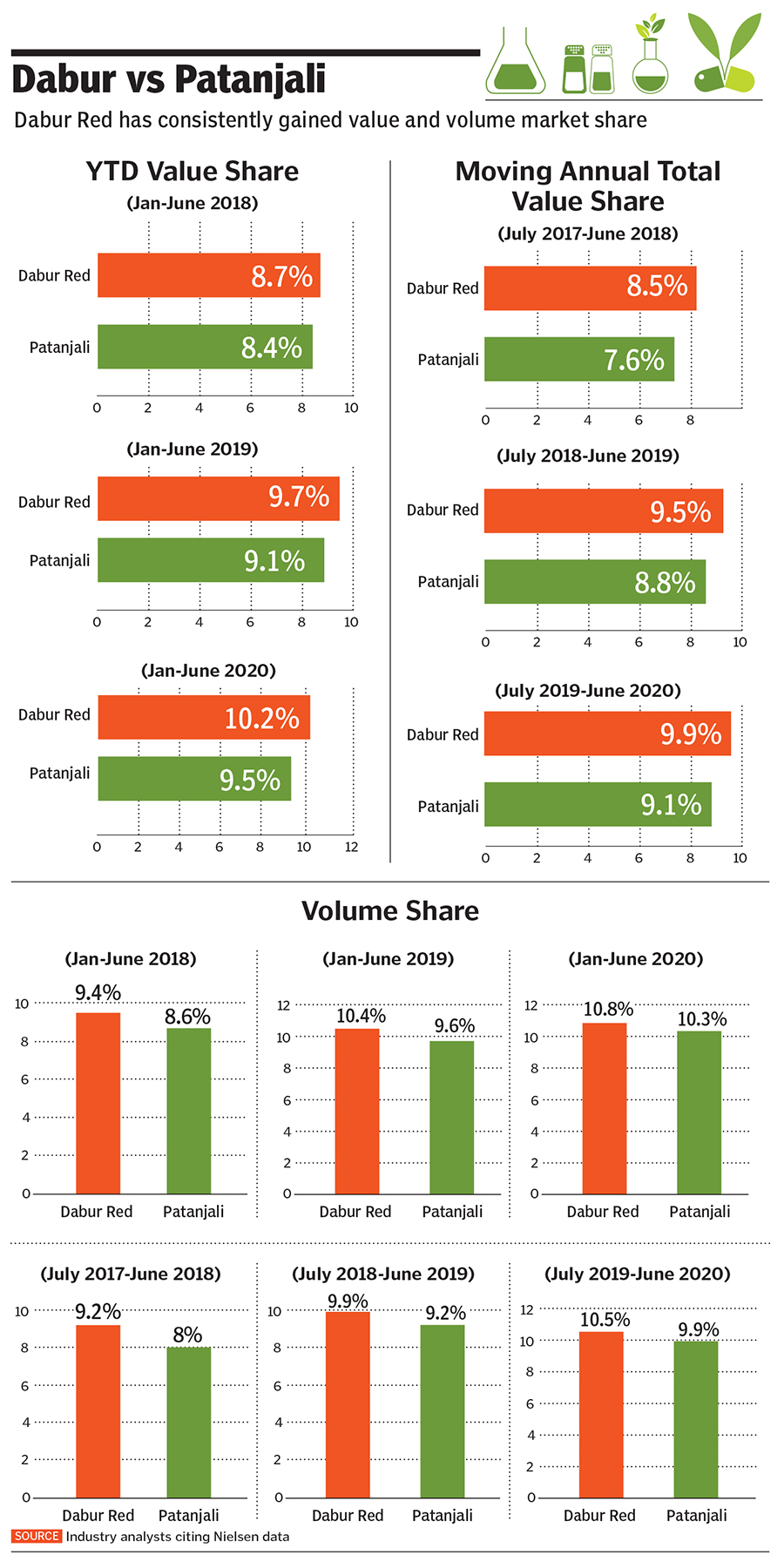

Cut to 2020. Dabur Red has become a ₹1,000-crore brand, weathered the Patanjali storm and stayed ahead of Dant Kanti, and is now closing in on its nearest rival Closeup, which is second in the pecking order after Colgate (see box).

While South India happens to be the biggest market for Red, East comes second, followed by the West and North India. In fact, in states like Odisha and Andhra Pradesh, Red is the leading brand. “We have sounded a red alert, and will soon become the second biggest,” says Malhotra.

While South India happens to be the biggest market for Red, East comes second, followed by the West and North India. In fact, in states like Odisha and Andhra Pradesh, Red is the leading brand. “We have sounded a red alert, and will soon become the second biggest,” says Malhotra.

The confidence, and the aggression, not only stems from what Red has done over the decade, but also from a glowing report card during the pandemic. In the first quarter (April-June) of fiscal 2021, while the toothpaste category grew by a modest 2.6 percent, Red outperformed the category with 8.1 percent growth. In some Hindi-speaking markets where Red is on a weak footing, Dabur has rolled out another brand, Dant Rakshak.

While the intent clearly is to widen the gap with Patanjali’s Dant Kanti, which is still close on the heels, the strategy is to have a flanking brand with low price point. While Red is priced at ₹50 for 100 gram, Patanjali was occupying the sweet spot of ₹40. Now Dant Rakshak will plug that gap in the price band. The results, Malhotra points out, are encouraging. “There is a 20 to 30 percent repeat (purchase),” he says.

Repeat buying was something that Dabur banked on heavily to push Red during the initial days. “Our target group was loyal manjan users,” points out Malhotra. There were also some fence sitters—those who had upgraded from powder to white paste, but were still yearning for a natural and ayurvedic offering. “We targeted this small niche as well,” he says. Though Red was premium in terms of pricing to Colgate, what worked in its favour was stickiness. “Those who tried didn’t go back,” says Malhotra. The first five years, he lets on, was a dream run. “The consumers amply rewarded us.”

In 2008, Red faced its first big challenge. The law of diminishing returns started to set in; though it had its sizeable base of loyal users, what was needed to grow was a new set of buyers, which was hard to find. Dabur changed its positioning, started talking about dental problems and how Red was better placed to solve them; and the company launched a series of campaigns and consumer activations. It also focussed on children with a massive school contact programme.

For adults, over the next few years, it went bolder with a toothpaste exchange programme. Bring the white tube and get a Red. ‘White toothpaste is chalk. Would you like to buy a chalk or Red?’ was another campaign to take the leader head-on. “We had gained confidence and we knew we can fight Colgate,” recalls Malhotra.

From 3.7 percent market value share in 2010-11, Red inched to 4.6 percent in 2013-14. Reason: The toothpaste category was overwhelmingly white, and takers for ayurvedic toothpaste were small in size. Then came the Patanjali storm.

For Dabur, it turned out to be a massive tailwind as the Baba Ramdev-backed toothpaste widened the category of natural, herbal and ayurvedic (HNA) toothpaste. While before Patanjali’s entry only 2 percent of the toothpaste market was HNA, it now stands at almost 30 percent, says Malhotra. Patanjali, he lets on, expanded the market, and Red was the biggest beneficiary.

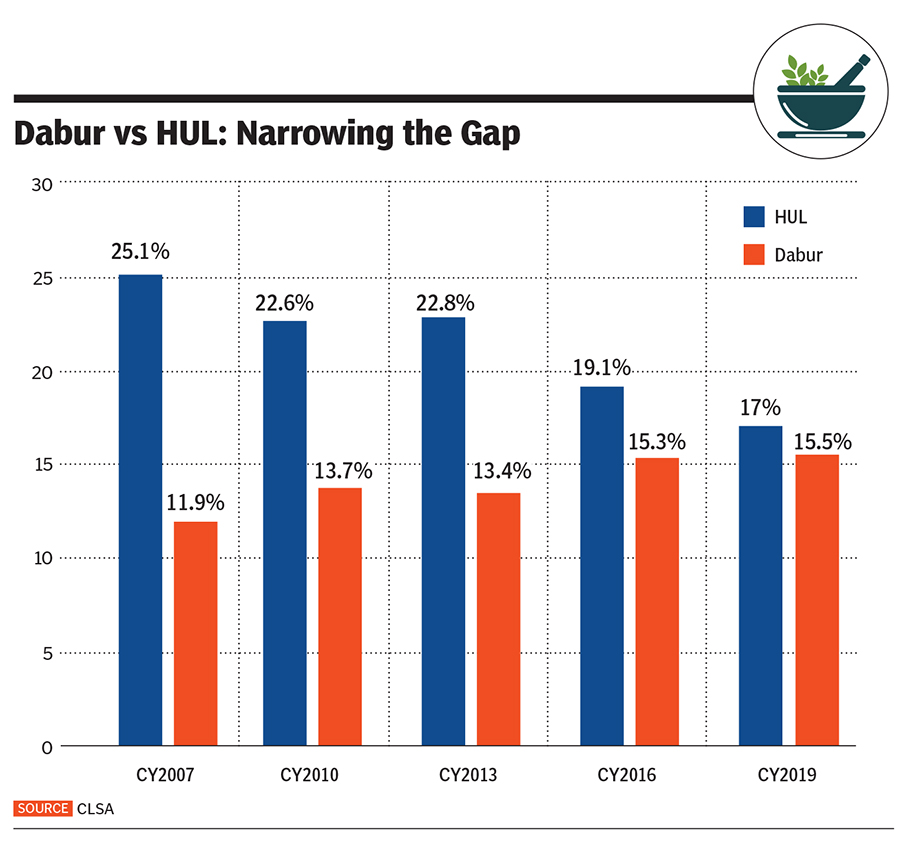

The faster growth in natural, global brokerage firm CLSA points out in its recent report, will remain. Colgate, the report maintains, with a wider play across categories and limited success in natural, has been losing share.

Patanjali, reckon FMCG experts, has turned out to be the biggest blessing for Dabur. With Patanjali driving home the advantages of ayurvedic products, Red stood to gain. “Not only did the tooth powder users upgrade to paste but also many who were looking for a more natural alternative switched to Red,” says KS Narayanan, food and beverage expert.

A sustained branding and advertising campaign over the last two years also helped in pushing market share. Take, for instance, the ‘Chaubey Ji’ campaign rolled out last year during the cricket World Cup. Using the colloquial term ‘chaba jayenge (chew them out)’, the brand reached out to consumers in a witty manner.

That Dabur survived and thrived for so long, point out brand analysts, underlines its army of loyal customers. In a market dominated by white toothpaste (read Colgate), Red established a distinction, first in terms of colour and then in terms of efficacy and concoction.

“Strangely, the ayurvedic appeal comes last,” says Harish Bijoor, who runs an eponymous brand consulting firm. To a country looking for a hard-working toothpaste that did not cost the Earth, Red had brand appeal, came from a reliable home of brands, and delivered. Red, Bijoor stresses, did well in small towns and villages. “In many ways that is where the real consumption lies,” he says. Gradually, Red made inroads into the bigger cities.

Red resonates with hinterland. Most hard-working brands in rural and Tier II India colour code themselves red. “We have Red label in tea, red Eveready in batteries, and red Lifeuboy soap,” says Bijoor. The colour red, he explains, is all about the basic, hard-working brand and the not-so-expensive in terms of imagery and delivery. “Dabur Red swims in this category of brands,” he says.

Malhotra, for his part, is unapologetic about the massive appeal the brand enjoys in smaller towns and villages. “We don’t want to make all brands urban. We are happy with Red,” he says. It is a big hit with the masses, over 70 percent of population still lives in rural areas, and that’s where the opportunity is, he reckons.

Malhotra, though, knows that the next big challenge for the brand is wooing millennials. Red in gel form had a promising beginning but started to fade in the cities against the onslaught of Closeup. Malhotra explains why the category of gel is different.

“It’s about freshness and white teeth,” he says. The buyers of gel are not looking for dental solutions. Red, he informs, is revamping the product, packaging and positioning of gel. “We are revamping it and rolling it out soon,” he says, adding that Red would also enter into many oral care categories. “We will paint the town red,” he says.

Comments