https://www.telegraphindia.com/culture/heritage/future-of-the-past/cid/1800367

Future of the Past

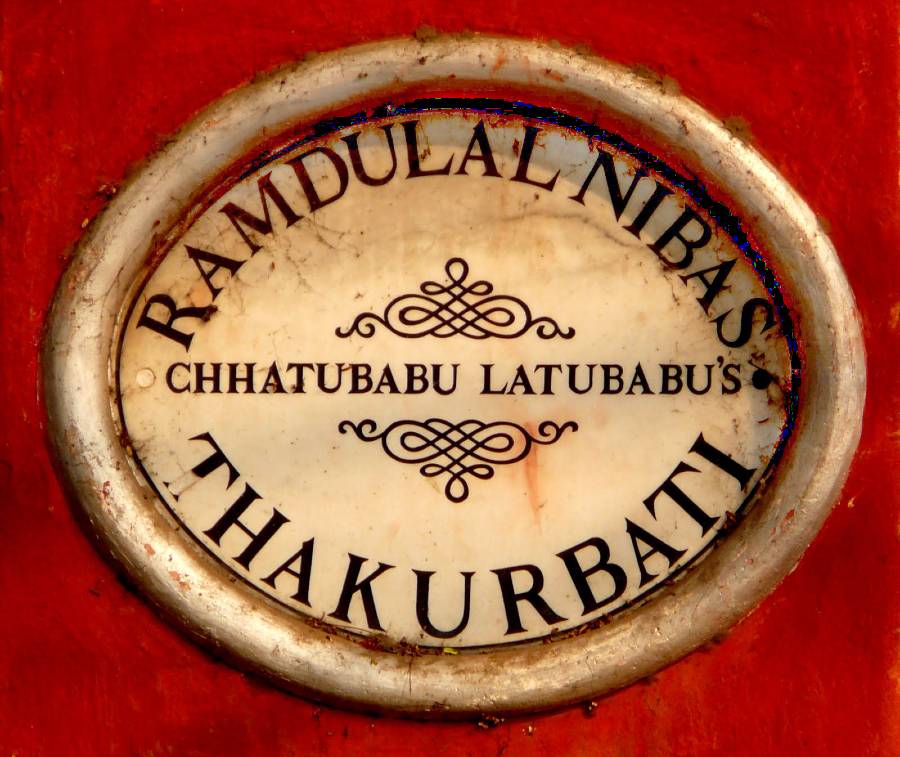

Pre-pandemic. The heritage industry of Calcutta was booming. Yes, the heritage industry. A little more than 200 guided tours — walking tours, cultural tours, archaeological tours, food tours, photography tours — run by individuals, community groups, private companies and institutions. Hooghly’s Flower Fest tour by Calcutta Photo Tours; Confluence of Cultures — Bow Barracks to Burrabazar walk by Calcutta Walks; Cruise into the Past: A Morning Heritage Cruise by the Heritage Walk Calcutta; Cycle the Kolkata Wetlands and Amazing Views by Shirish Poddar; Slum Walking Tour by Let’s Meet Up Tours; Walking With Ghosts (a midnight tour) by Anthony Khatchaturian; a two-hour traditional Bengali meal in a private Calcutta home by Travelling Spoon; The Dying Ghats walk; South Park Street Cemetery walk; Ramzan food walk… Walks and tours are used interchangeably, but the thing to remember is that while all walks are tours, all tours are not walks. In any case, these things, mostly ticketed and ranging from Rs 150 to Rs 5,000, turned focus on 30-plus neighbourhoods. Chitpur, Strand Road, Kidderpore, Metiabruz, Tiretti Bazar, Shyambazar, Park Street, Dalhousie... They told the stories of at least 15 communities — Anglo-Indians, Jews, Parsis, Chinese, Marwaris, Armenians, Gujaratis, South Indians. Of vanishing textiles — muslin, khadi. Of traditional art forms such as kantha stitch, patachitra, putul-making, terracotta, and a rich and mixed culinary heritage. Big, small and nondescript places with historical backstories stirred awake to find themselves buzzing with activity and attention. The 94-year-old Calcutta South India Club now has a coffee shop on its premises, the American online vacation rental company Airbnb acquired some old properties, Victoria Memorial came to host a lit fest, as did Tollygunge Club and St. John’s Anglican Church, the old RBI building in Dalhousie Square turned into a currency museum, and the iconic Old Currency Building got a makeover and was reborn an exhibition hub. Then there were cultural projects, CSR funded-projects and intervention projects funded by cultural organisations. The clientele included tourists — foreign and domestic — and locals. The most footfalls were clocked between October and March. In an industry-lean geography, all of this created new job opportunities — photographers, researchers, bloggers, social media strategists, web designers, videographers, content creators — and lent relevance to ones that had long passed into the city’s blind spot — the tongawala, the rickshawala, the ittarwala. In the 2016 Bengali film Praktan, a Prosenjit-Rituparna starrer, the protagonist was someone who conducted heritage walks. In the 2018 thriller Alinagarer Golokdhadha, the hero was heritage. To borrow one more time from the movies, Calcutta’s bhabishyot now seemed to hinge on its bhoot, or past.

Calcutta had the highest growth in foreign tourist arrivals — 13.5 per cent — among all the metro cities in India between April and December 2019. Entwined as it is with travel and tourism, post the pandemic, the heritage industry screeched to a halt. Says Ramanuj, one of the “explorers” or guides of Calcutta Walks, “Before Covid-19 happened, we used to achieve a target of 1,000 walks annually. But things have changed.” Manjit Singh Hoonjan, who founded the Calcutta Photo Tours nearly a decade ago, predicts a longer pause than the other industries. He retorts, “If it were virtually possible, do you think people would travel for so many hours, endure multiple flights and layovers?

Mohua Shome Lalvani was conducting walks in the city long before they were the “it” thing. Mohua’s walks were peregrinations. She says, “We were doing it for ourselves. Just out of curiosity and to know our city better.” There was no fee attached. But around the same time, Iftekhar Ahsan launched Calcutta Walks and it was quite the opposite. Iftekhar tells The Telegraph, “A decade ago, online travel portals did not have a category titled ‘walks’ for Calcutta. We were clubbed under hotels.” He started with the Dalhousie Square walk. And today, the scroll-down menu of the Calcutta Walks site offers six modes, nine themes, and one heritage stay. Client testimonials are datelined Connecticut, Dubai, the UK, Netherlands, Chicago, Bangladesh, Paris, Berlin.

“They want to see India outside Taj Mahal, Varanasi, Wagah Border,” says Ramanuj. “When they do a culinary walk they really want to see the making of the kathi kebab roll at Nizam’s. They want to understand how Bengali food is served course by course. They really want to know stories about places, stories that are not available on Google. I take them to Nimtala Ghat near Bhoothnath to have litti chokha and cha. They want to shop for shankha-pala (traditional bangles and markers of a married woman in Bengal). Sometimes I have arranged sari-wearing sessions for them,” he adds. “For us, international clients are important. It is the constant funding we need to survive,” says Iftekhar.

Speaking of survival, as the heritage industry continued to experiment and expand, green shoots raised their heads. Of course, not everything produced direct economic benefits. For instance, for the last 60 years on Sunday mornings the Chinese community of Tiretti Bazar in central Calcutta puts out a breakfast spread for anyone who cares to stop by. In 2016, The Community Art Project (TCAP) entered the scene and it highlighted the story of the Indian Chinese community. Says Swati Mishra of TCAP, “People started taking ownership of their public spaces… We had people from the community coming up to conduct art workshops, food pop-ups and even a heritage walk.”

Atreyee Basak and Poulomee Auddy are founders of The Ganges Walk – Rediscovering Calcutta. Since 2018, they have been doing walks and one such is exploring the Dying Ghats Walk, a three-hour affair beginning at Armenian Ghat and ending at Nimtala. It focuses on the tales of ghats or riverfronts. Atreyee says many students of history and architecture are now keen to be a part of the heritage industry. Says Poulomee, “They approach us for internships… We are here to give back to the city the essence with which it was carved into being.”

Sumona Chakravarty, founder of Hamdasti, a community-based arts organisation, says, “There are lots of artists who are a part of this (heritage churn). They may not be directly employed, but given the lack of institutional spaces for supporting art, they have found these abandoned buildings and reinvented them as artist-run and pop-up spaces.”

Chelsea McGill and Tathagata Neogi founded the Heritage Walk Calcutta in 2017 — it has since been renamed Immersive Trails. Chelsea says, “We wanted our venture to be a self-sustaining social enterprise... This was why we chose to start as a for-profit enterprise. A non-profit model would have to depend on donations and external sources of funding often with riders... But as a private limited company we generate funds ourselves. We then invest the money back in researching and creating new experiences as well as building a robust team of experts and interns.”

Jayanta Sengupta, secretary and curator of Victoria Memorial Hall (VMH), calls this phenomenon “a fortuitous convergence of new interests and avenues related to heritage”. Victoria Memorial was possibly never lacking in footfall and attention, but now, to use Sengupta’s words, they tried to “reinvent VMH as a safe, inclusive, pluralist-in-spirit space for a wide range of conversations”. He adds, “It’s an advantage to have spaces that lend grandeur (front steps) as well as intimacy for smaller conversations or concerts (the colonnaded quadrangles on the sides).”

The events hosted at VMH showcased not just its own grandeur but the grandeur of Calcutta and by extension of Bengal. G.M. Kapur of Intach talks about how riding the heritage surge people from Krishnagar, Murshidabad started contacting him for advice on monetising heritage properties. It seems even tea estates had started to use a colonial bungalow or two for homestays.

Says Swati, “This is the best thing to come out of it all. Heritage and culture are no longer limited to the elite galleries but are there in the public spaces for everyone to access. This is how it should be, beneficial both ways.”

Shalini Bansal is one of the co-founders of HopOn India, an app-based audio-guided tour. They had launched three Calcutta walks in 2018 — Pathuriaghata – Finding the Tagores, Calcutta Sports Walk – The Fabled Maidan and the Dalhousie or BBD Bag Walking Tour. Shalini admits, “The industry is suffering like never before.” Sengupta of VMH says, “We, as a government institution, are insulated from layoffs and furloughs, but there are many heritage institutions that are struggling.”

Shalini, however, balances this with talk of the advantages of a “digital product”. Indeed, most heritage outfits have started virtual walks, diversified into talks, 3D tours, exhibitions. HWC is one of them. It seems for the first 50 days of the lockdown, they did a daily trivia on their social media pages. They also conducted capacity building workshops — all paid — via video conferencing for “non-experts who want to learn how to record and understand heritage in their own surroundings”. Shalini believes now people will want to travel to places nearer home much more. Manjit seconds that. Ramanuj says, “We have started doing some walks since September. We did five walks each in September, October and November. Locals are the audience now. We do walks early in the morning and there are less people and crowds.”

But Sengupta provides what is possibly the buzzword, the mantra to rescue the ghost of an industry and nudge it towards a brighter bhabishyot. “Collaboration,” he says. “We need more collaboration, more joint programming, more concerted promotion of those aspects of our heritage that are facing a crisis. Our assets and skills are intact, but we need to save the people associated with them.”

Comments