- https://bigthink.com/the-learning-curve/5-stoic-quotes-to-help-you-through-difficult-times/?utm_source=pocket-newtab-intl-en

- It can sometimes feel as though we live in uniquely difficult times.

- Zeno of Citium developed Stoicism to teach how to face such challenges.

- Later Stoic philosophers offered pertinent advice on how to adjust our perception around struggles and live a fulfilling life.

It can sometimes feel as though we are living through uniquely difficult times. Wars, disease, economic upheavals, and political strife dominate news headlines. Traditions, once the terra firma of our lives, have split along cultural fault lines and are shifting widely. And the lessons imparted to us by our parents seem completely out of touch with the challenges we face daily.

In short, there seems to be much cause for sadness, despondence, and being overwhelmed by life.

We are not special in this regard, though. Our modern circumstances may be idiomatic — Plato worried over the harms of pervasive poetry; not social media would have thrown him for a loop — but strife and struggle have been universals of human history. Every generation has had to endure both to various degrees.

Amid those struggles, our ancestors developed and refined a variety of traditions to help them persevere, and we can draw on those traditions to give us a leg up in facing our contemporary challenges. These traditions include the religious doctrine of Buddhism from India, the philosophy of Chinese Taoism, the humanism of the European Enlightenment, and the topic of today’s article, the Stoicism of Hellenistic Greece.

A short history of Stoicism

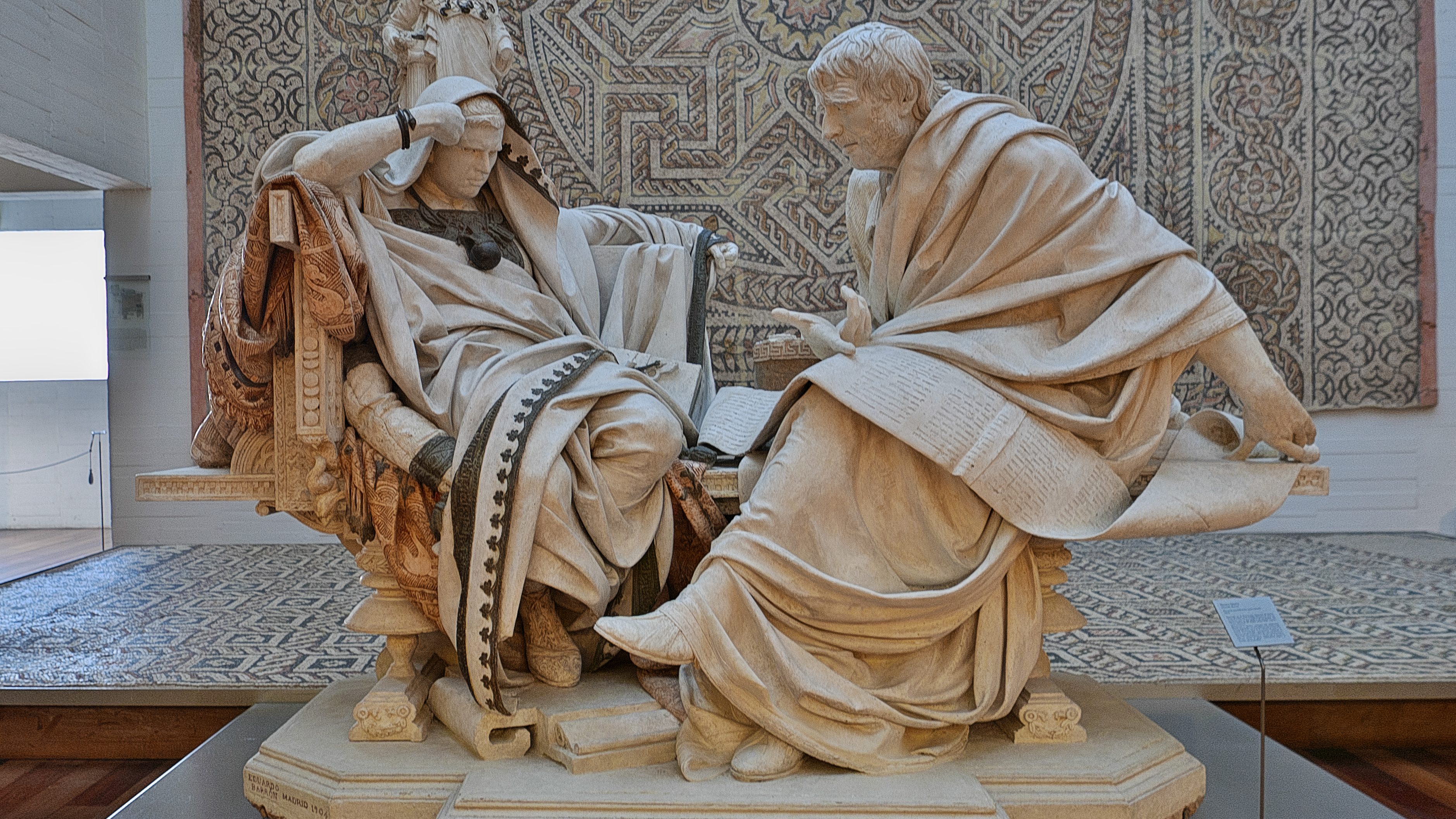

Zeno of Citium founded Stoicism in the 3rd century BC. He lived in Athens and lectured in the open market at a place called the stoa poikile — literally “painted porch” and Stoicism’s namesake. That’s important for understanding Zeno’s philosophy because this period of history represented a time of profound change and unrest.

In 323 BC, Alexander the Great died without an obvious heir, leaving his kingdom to be fought over and subsequently carved up by his generals. As a result, the Greek poleis became subsumed by larger political entities run by professional bureaucrats. Where once Greek freemen operated in democratic city-states, they were now entangled in large, more impersonal empires.

In the words of Chloè Valdary, founder of Theory of Enchantment, it was an era of “existential homelessness,” and many Greeks found themselves saddled with traditions and a worldview that no longer matched the social and political disorder surrounding them.

Within that existential despair, Stoicism developed as a unified philosophy that sought to understand the essence of knowledge and the natural order of the cosmos. From that pursuit, the Stoics derived an ethic that, in the words of philosopher Simon Blackburn, focused on self-sufficiency, benevolent calm, and a near-indifference to pain, poverty, and death. This would in turn lead to happiness (in the eudaimonic sense of the word).

As Stoicism moved from the Hellenistic period into the Roman world, its ethics took center stage, becoming the reason for the philosophy. It centered on how the practice of virtue could be applied to everyday living through sound judgment, proper character, and the rejection of vice. It does this by considering where we should and shouldn’t place our efforts. Today, that emphasis on engaging with everyday life has seen Stoicism revived as a kind of practical philosophy. It draws strongly from Stoicism’s later Roman practitioners and is often used in tandem with other strategies for coping and emotional regulation.

As such, you can use the quotes below without having to dust off earlier Stoic concepts like the phantasia kataleptikē or the logos spermatikos. (So no worries if you haven’t brushed up on your ancient Greek.)

“Things do not touch the soul, for they are external and remain immovable.”

– Marcus Aurelius

As Valdary noted in an interview: “Stoicism is all about getting us in [the] right relationship with the things that we can control and we can’t control.”

For example, Zeno’s Greek contemporaries couldn’t control Alexander the Great’s death or the ensuing social upheaval. Such things, as Aurelius put it, should be considered external and immovable. They do not touch a person’s soul because where someone lacks control, they also lack responsibility.

By worrying needlessly over what we aren’t responsible for, we distract ourselves from the things we can control. And if we can’t control such events, then why should they cause us undue suffering? If we aren’t responsible for something, why should it affect our happiness and fulfillment?

In the same section of Meditations (Book IV), Aurelius also warns that the world is always changing, and we can’t stop that from happening. We can only influence how we think and react to that change. As he writes, “The universe is transformation: life is opinion.”

“For as wood is the material of the carpenter, bronze that of the statuary, just so each man’s own life is the subject-matter of the art of living.”

– Epictetus

Now, Aurelius doesn’t mean we should live lives as moral recluses in total passivity. Far from it. We can (and should) strive to enrich our lives and the world in virtuous ways. The Stoics did this themselves when they taught their philosophy.

However, we need to understand where our control lies, and that responsibility is primarily with ourselves. Just as a carpenter shapes wood, Epictetus writes, so too are we responsible for the art of living. That art includes how we respond to our thoughts, our emotions, and the world outside of us.

In particular, this quote comes from a moment in The Discourses where Epictetus is consulting a man whose brother is upset with him. Like a true Stoic, Epictetus’s advice is for the man to tend to his emotional state and act according to his governing principles.

As for the brother: “Bring him to me, and I will talk to him,” Epictetus said, “but I have nothing to say to you on the subject of his anger.”

“We suffer more often in the imagination than in reality.”

– Seneca

When our minds are filled with those “external” and “immovable” qualities of life, we often catastrophize more than is appropriate.

We exaggerate how bad a sickness is by doom-scrolling through Google results before visiting the doctor. We pronounce that the world is going to hell whenever an election doesn’t swing our party’s way. And we anticipate that a difficult conversation will be the end of our friendship. None of which, according to Seneca, is helpful in the least.

In Letters of a Stoic (Epistle XIII), the Stoic philosopher advises his interlocutor, Lucilius, that such catastrophizing does no good. It only makes us unhappy before the crisis, assuming the crisis comes at all. Instead, we should reign in our mind’s calamitous predictions and handle what’s before us with the proper care and attention.

Aurelius backs up Seneca on this point. As he notes in The Meditations (Book II), “Those who do not observe the movements of their own minds must, of necessity, be unhappy.”

Neither Seneca nor Aurelius are saying you’ll never feel pain, sorry, stress, anger, or a host of other unwelcome emotions. Outside events, as well as our internal struggles, will still give rise to these feelings naturally. They are part of the materials of the art of living, too.

Rather, they teach us to not let our emotions grow strong enough to overwhelm us or blind us to reason. Better to understand the source of the emotion and treat it with the proper care than to continue suffering in the mind.

“What do you think that Hercules would have been if there had not been such a lion, and hydra, and stag, and boar, and certain unjust and bestial men, whom Hercules used to drive away and clear out?”

– Epictetus

Epictetus teaches that while difficult times are often, well, difficult, they can also be a means toward growth and self-improvement. In The Discourses (Book I), he exemplifies this in the example of Hercules. Had Hercules not undergone his 12 labors, Epictetus contends, he would not have become the legendary Hercules. He would have wallowed his life away dreaming instead.

One can say the same of the Greeks during the Hellenistic period. While it was a time of immense social and political tumult, it was also a cultural renaissance that birthed new ways of thinking and expression.

New forms of art, music, and literature emerged. Science and invention reached new heights under thinkers such as Euclid and Archimedes. And alongside Stoicism, the era gave birth to the philosophies of Epicureanism and Neoplatonism as well.

Modern science backs up Epictetus’s claim. According to Paul Bloom, a professor of psychology at Yale University, research shows that the most meaningful jobs aren’t the most luxurious, highest paying, or those of the highest status. Instead, they are jobs that involve struggle and difficulty, such as being an education or medical professional.

“I think that the way people think about a meaningful life is that it requires some degree of suffering,” Bloom said in an interview. “That suffering could be physical pain. It could be difficult; it could be worrying. It could be the possibility of failure. But stripped of that, the experience isn’t meaningful. We need pain and suffering to have rich and happy lives.”

With that said, Bloom and Epictetus both put caveats on this dictum. Epictetus warns that a person shouldn’t go searching for lions and hydras simply to introduce suffering to their lives. Similarly, Bloom distinguishes between “chosen suffering” (such as exercise) and “unchosen suffering” (such as chronic pain from disease).

But we shouldn’t turn away from suffering simply because it’s difficult, painful, or includes the possibility of failure as many of life’s great achievements can be found within that struggle.

“The first thing which philosophy undertakes to give is fellow-feeling with all men; in other words, sympathy and sociability.”

– Seneca

So far, we’ve looked at how the Stoics taught individuals to approach difficult times. That may make it seem as though Stoicism is some kind of proto-libertarian philosophy. Just take care of yourself and let the rest of the world take care of itself.

That characterization, while common, is also misleading. As this quote from Seneca’s letters (Epistle V) makes clear, Stoicism advises us to be there for others, and the way we can do that is through sympathy and companionship.

Consider friendship. In Epistle IX, Seneca writes: “For what purpose, then, do I make a man my friend? In order to have someone for whom I may die, whom I may follow into exile, against whose death I may stake my own life, and pay the pledge, too.”

For Seneca, a friend isn’t someone who can come to the rescue and solve your problems for you. Like Epictetus with his angry brothers, Seneca can’t save his friend from exile or death. He can’t change a friend’s mind or live his life for him. Nor would Seneca expect a friend to take responsibility for his problems or emotions either.

Instead, a friend is someone whom we experience the shared experiences of life with. They can make the good times better, but they also stand by us during life’s struggles. They can listen to our ideas and point out our blind spots. Their compassion can help us cope with life’s losses.

In other words, simply through sympathy and companionship, a friend becomes a source of immense strength that helps us along our individual paths. And that can be true of any relationship.

“[Compassion] is about learning how to be with ourselves and our fellow humans in their suffering,” Valdery said. “Stoicism is as much about having compassion for others as self-compassion on our individual journeys toward fulfillment and happiness.”

Comments